No Slides Entered.

How Studying Abroad Expanded My Conservation Perspective

How much more would our understanding of conservation grow if we experienced biodiversity on a global scale?

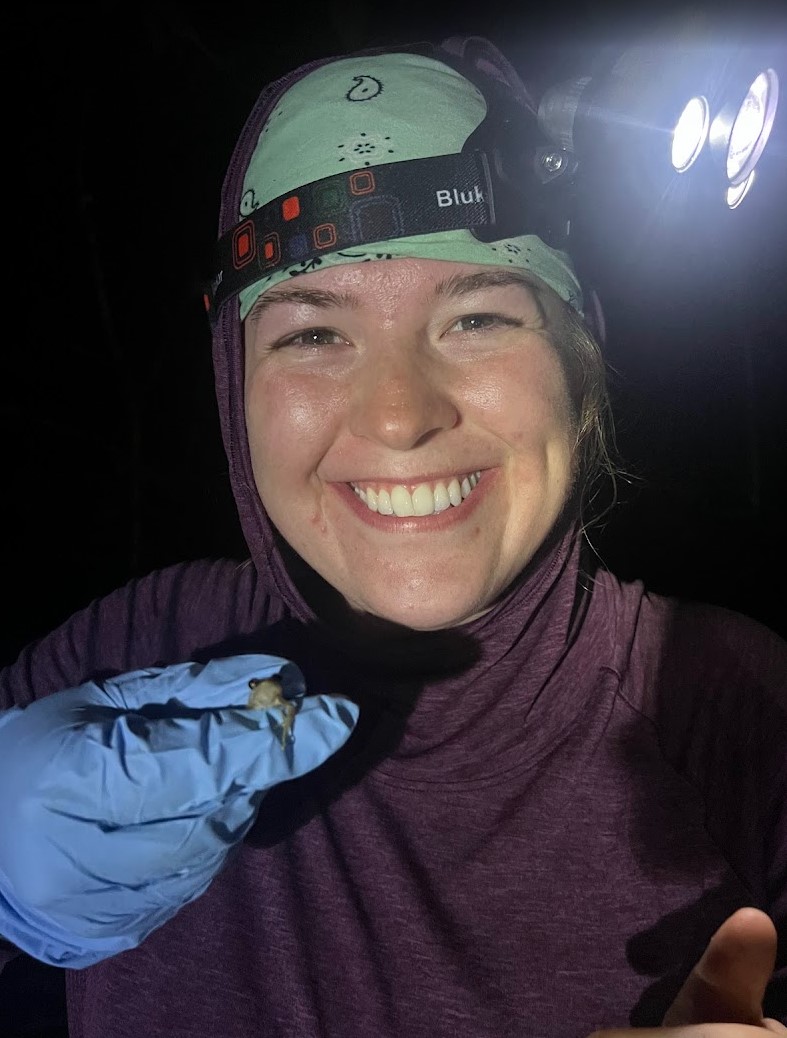

By Melyssa Riggs

Experiencing firsthand the wide variety of life native to Borneo, Malaysia, deepened my belief in conservation. Borneo’s massive rainforests are home to thousands of species found nowhere else, which include critically endangered wildlife like the Bornean orangutan, pygmy elephant, Sunda pangolin, and countless more. Despite being home to hundreds of unique plants and animals, this biodiversity hotspot faces intense pressure from palm oil expansion, logging, and widespread deforestation, making it a focal point for global conservation efforts.

Studying abroad in Malaysia allowed me to step beyond the familiar landscapes of the American West and immerse myself in conservation from a global perspective. As a wildlife and fisheries management student, I wanted to understand how other countries approach habitat loss, species protection, and sustainability. My study abroad program focused on habitat restoration and biodiversity monitoring, offering firsthand experience in one of the most ecologically important regions on the planet. During the program, my classmates and I lived at the Danau Girang Field Centre, a research station within the Lower Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary in the Sabah region of Borneo. The center brought together an inspiring mix of Malaysian and UK university students, researchers, and local field staff. Working alongside people with such diverse backgrounds and a shared commitment to the environment made everything we did feel connected and purposeful.

We started our fieldwork by exploring restoration sites at various stages of recovery after palm oil plantations were removed, and by comparing them to a control site within an active plantation. We conducted vegetation surveys at each site, measuring canopy and subcanopy cover, examining understory density, and documenting plant species. These surveys helped illustrate how forest structure changes over time and emphasised the importance of long-term monitoring in restoration success. Alongside this, we carried out biodiversity surveys focused on birds, mammals, frogs, and arthropods. Each site offered a distinct ecological snapshot, with disturbed forests showing a higher abundance of generalist species, while undisturbed rainforest supported more specialist species. Even simple night walks revealed an impressive range of biodiversity, from amphibians and insects along the forest floor to bats flying overhead and small mammals moving through the understory. River surveys added another layer of activity, with monkeys, birds, and crocodiles occupying the forest’s edge. Yet even with all that we observed, it was clear that these encounters represented only a fraction of the biodiversity actually present within the rainforest.

Working alongside local community members became one of the most meaningful parts of the experience. Their dedication to maintaining the tree nursery demonstrated just how much persistence and coordination effective restoration requires. By helping plant native seedlings in reforestation areas, we were able to contribute in a small way to the long-term health of the ecosystem and its wildlife. These moments also made it clear that conservation is as much about people as it is about the environment. Through our interactions with the local staff, we were able to participate in traditional dances, learn how they played their musical instruments, and hear the stories behind them. To me, this experience underscored how cultural identity and environmental stewardship are deeply connected. Recognising this human dimension helped me better understand the broader pressures shaping Sabah’s landscapes. A visit to an active palm oil plantation and processing facility revealed a more complex reality than I had anticipated. While palm oil contributes significantly to deforestation, it is also a cornerstone of Sabah’s economy, providing employment and stability for many communities. Some plantations have begun collaborating with conservationists to reduce human–wildlife conflict, support restoration projects, and implement more sustainable practices. Observing this interplay between economic necessity and ecological responsibility highlighted the importance of integrating, rather than opposing, major industries in effective conservation.

Throughout the program, we assisted university students with diverse research projects from tracking pangolins and flat-headed cats to studying butterfly–fungi interactions and comparing carbon sequestration in restored forests versus plantations. These projects demonstrated how interconnected conservation research can be and how each study, no matter how focused, contributes to a broader ecological understanding. What surprised me most was how often Borneo reminded me of home. In Sabah, palm oil plantations create significant habitat fragmentation. In Wyoming, a very different industry of energy development creates similar fragmentation through roads, pipelines, wind farms, and drilling sites. Despite being worlds apart, both places face shared challenges: habitat loss, disrupted wildlife movement, and rising human–wildlife conflict. Recognising these parallels broadened my perspective and highlighted how conservation issues transcend borders. We also examined the role of ecotourism as an alternative source of income. Ecotourism can bring economic benefits, educational opportunities, and increased support for wildlife protection. At the same time, it can lead to overcrowding of people and heightened human–wildlife conflict. A good example of these issues can be seen in places like Yellowstone or the Tetons. Understanding these trade-offs taught me that ecotourism must be carefully planned if it is to support conservation rather than harm it.

This experience shaped my academic and professional goals more than I expected. I gained new field skills, learned how conservation approaches differ across cultures, and became more confident working in diverse, international teams. Above all, I saw how essential collaboration is for conservation to succeed, whether it be locally or internationally. Studying abroad made me more adaptable, more curious, and more committed to contributing to conservation on a global scale.

I know that studying abroad can feel intimidating or financially impossible. Many students believe that international programs won’t fit into their academic paths or that global research isn’t relevant to their field. My experience proved the opposite: international fieldwork is not only relevant, but it is also transformative. I want others, especially students who feel unsure, to know these opportunities are within reach. The Gilman Scholarship is a major reason this experience was possible for me. The scholarship exists to make studying abroad accessible to students who may not otherwise have the chance. I hope that by sharing my story, other students will feel empowered to apply, to articulate their goals, describe their aspirations, and show how international learning can benefit themselves and their communities back home. My time in Borneo reshaped how I view conservation and my place within it. I learned that conservation starts locally. I saw how vital forest connectivity is for wildlife survival and how ecological challenges across the globe mirror those in our own backyards. Most importantly, I discovered that stepping outside familiar ecosystems is one of the most meaningful ways to grow as a wildlife biologist. Studying abroad in Malaysia taught me far more than field techniques. It broadened my perspective, strengthened my dedication to conservation, and inspired me to encourage others to pursue global learning. I hope my experiences motivate other students to explore study abroad opportunities, apply for scholarships like Gilman, and seek out the unforgettable lessons that come from learning across borders.

Acknowledgments: I would like to thank the Danau Girang Field Centre, the University of Wyoming Botany and Biodiversity Institute, the University of Wyoming Education Abroad office, and the Gilman Scholarship Program, along with Brent E. Ewers and Trevor Bloom, for making this study abroad experience possible.

Share This Post

Social Media

Latest News

Archives

- All

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- October 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- April 2023

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- October 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- January 2020

- March 2019